Graphic Design for Film, introduced via Annie Atkins and buttery hands

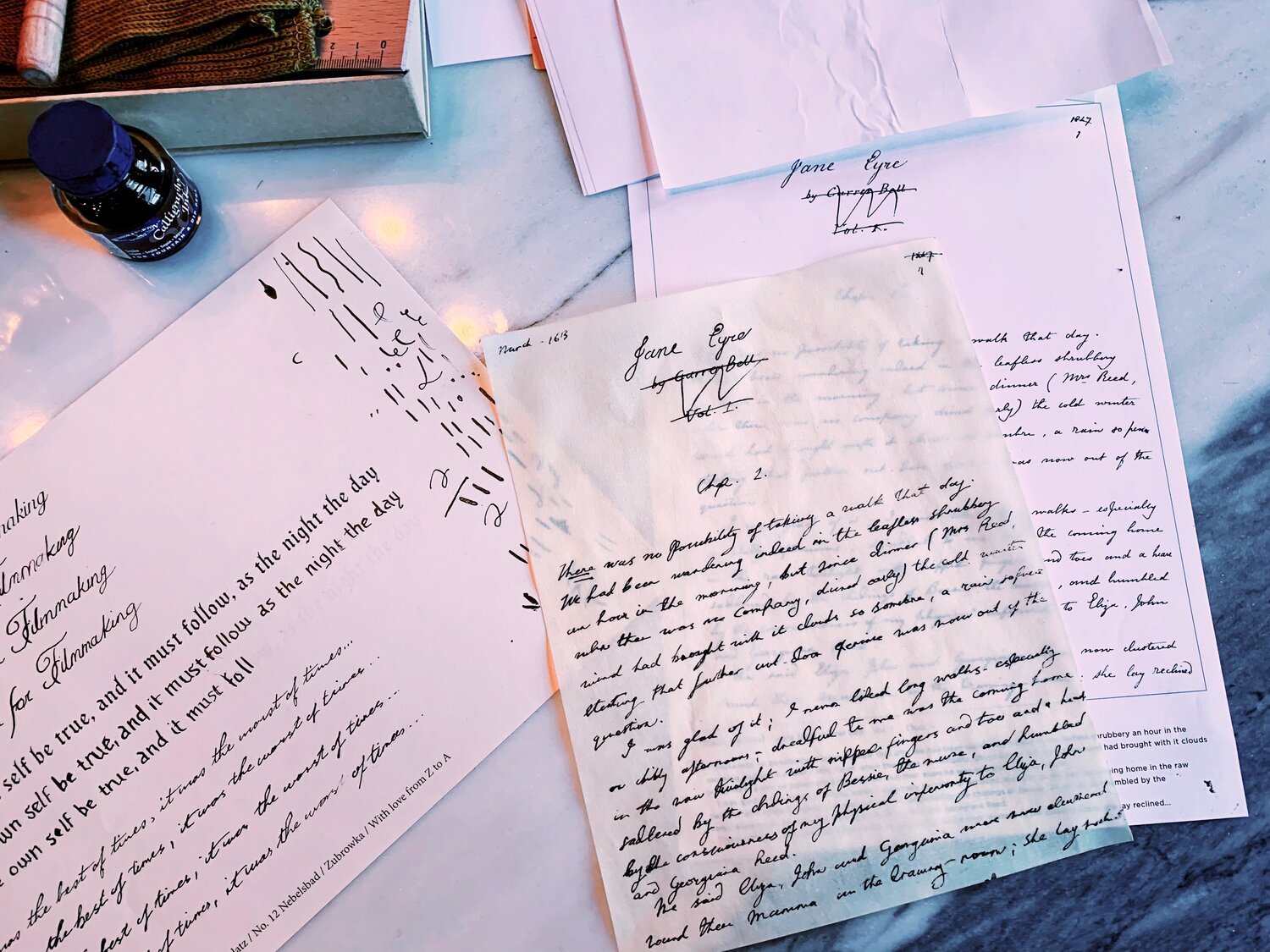

For as long as I can remember, I have been collecting vintage ephemera. While this has sometimes proven incredibly impractical – lugging boxes full to the brim with various bits of paper up and down stairs for every house move – every time I visited a new city, I couldn’t help forging a connection to that place via its dustiest abodes. I would rifle through flea markets, worm my way through rickety bookshops in the back-end of nowhere, and hunt down bougie hipster cafes for their loyalty cards.

There’s never really been any point to this collection. It’s made its way into a couple of collages but has otherwise presented a bit of an unanswered question in my life. Why did I have the incessant need to stuff my rucksack with old things? Why did I spend twenty quid on a newspaper from the 1800s? Did I not know I could buy AT LEAST one brunch for that money?! Luckily, upon attending Annie Atkins’ workshop on Design for Filmmaking, someone finally made some sense of it all for me.

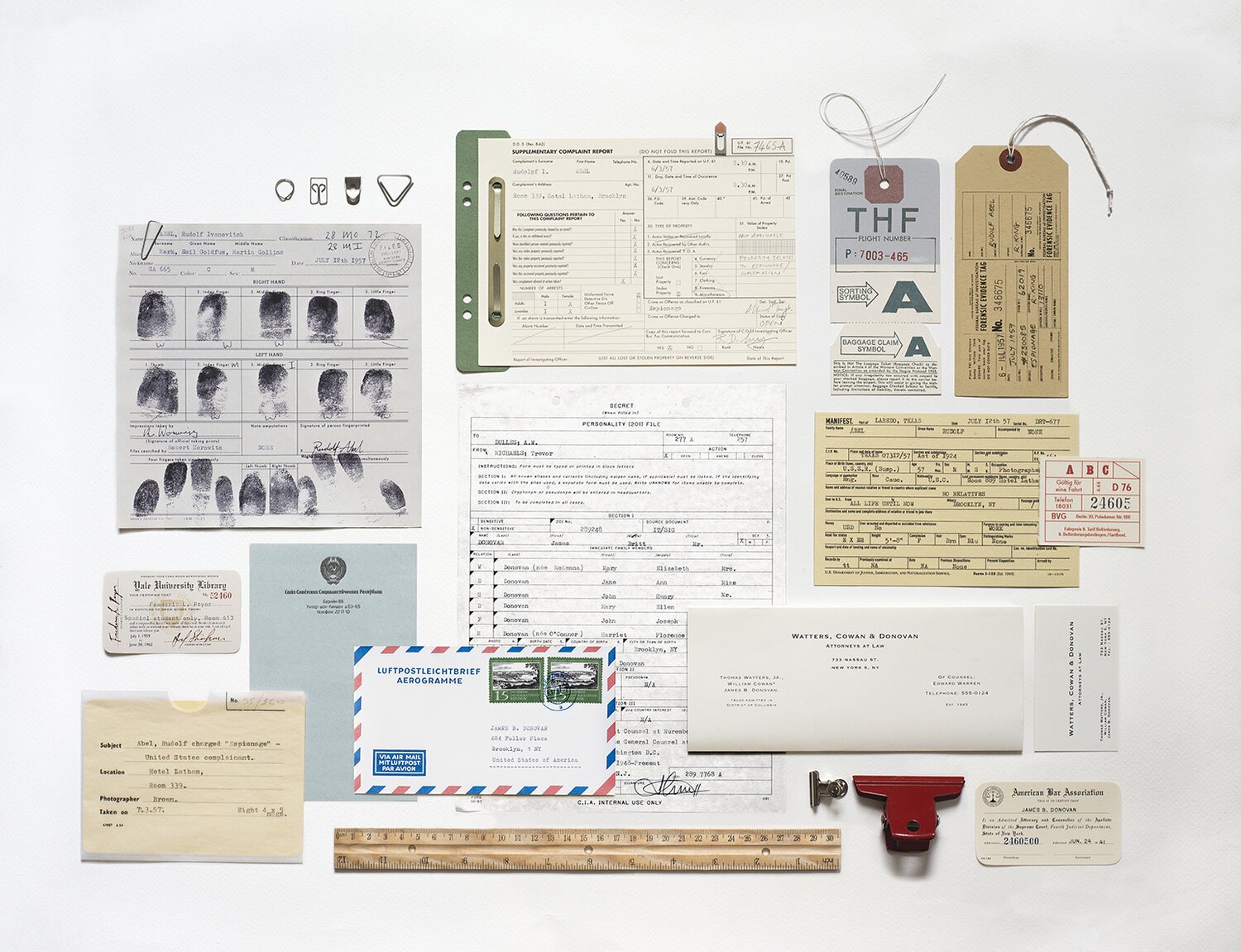

Annie has been described as a ‘master forger’. She creates graphic props for movies all over the world and is responsible for the famous pink Mendl’s Box in Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel, as well as tonnes of other beautiful pieces. Her credits include Bridge of Spies, The Boxtrolls, and The Tudors, amongst many others, and she runs workshops on design for filmmaking right from her Dublin studio. And you know what? It turns out I’m not the only one who finds old bits of paper fascinating.

Graphic design for film involves a lot of collecting old curios, an obsession with detail, and a lot of organisation. Three of my very favourite things if you discount Heinz Beans with Sausages… which arguably also belong in the category of old curios.

To start: what exactly is graphic design for film? It encompasses anything you see on screen that features words, patterns, illustrations or made out of paper. Every telegram, postcard, and newspaper that’s collected by a graphic designer working on a production provides a frame of reference with which to build a realistic, believable world – both for the audience and the cast. The devil really is in the details here, as half the things produced by graphic designers in art departments never see the light of day. They’re usually out of shot, hidden by another prop or a supporting artist’s head, and are generally not supposed to be the focus of any given scene. If you spent the entirety of The Sound of Music staring at an advert for eggs, someone’s probably not done a very good job (or you skipped breakfast).

The pieces produced also need to have a sense of character behind them. Graphic designers aren’t just making a sign; they’re contributing to creating a space in which that signwriter can exist. Throwing their own design instincts aside, they have to consider how each character would sign that birth certificate, stick down that family photograph or rip up that love letter. For designers outside the industry, learning graphic design for film is almost like re-learning how to design from scratch. Designers have to crack out the paint, or icing sugar, or quill, and work out just how they’d be held and used.

Annie’s workshop also covered various practical tips and tricks for ‘Faking It Until You Make It’ in the movies. Without going into too much detail (pay for the workshop, cheapskates), I learnt, with hands covered in butter*, that not every graphic designer is a master calligrapher, and not every illustrator can produce a copperplate etching. This came as a massive relief to me because, sometimes, my hands just won’t do what I expect of them. Draw a straight line? Sure, this one time, but the next time I do it you can bet it’ll look like an indecisive worm.

I came away from Annie’s workshop with a great sense of optimism and enthusiasm for graphic design for film. It no longer felt like a closed-door but, instead, like an accessible career path that encouraged questions, learning on the job and faking it when necessary. If this piques your interest at all, I highly recommend pre-ordering Annie’s book Fake Love Letters, Forged Telegrams, and Prison Escape Maps: Designing Graphic Props for Filmmaking. If it’s half as good as her workshop, it promises to be an absolutely cracking read.

*this is some sort of quaint English phrase you’ve never heard of, they actually were covered in butter. Some say the butter still remains on my hands to this day. Apparently it makes paper see-through.

This was part one in a series I’ve planned about how I took my fledgling steps into graphic design for film from Real World graphic design. It was reposted from October 2019. If you’ve found it faintly amusing or useful for reasons you don’t have to justify to anyone, especially yourself, consider doubling down and signing up for my newsletter. I promise strictly guff. A good old guff pact between two consenting adults.